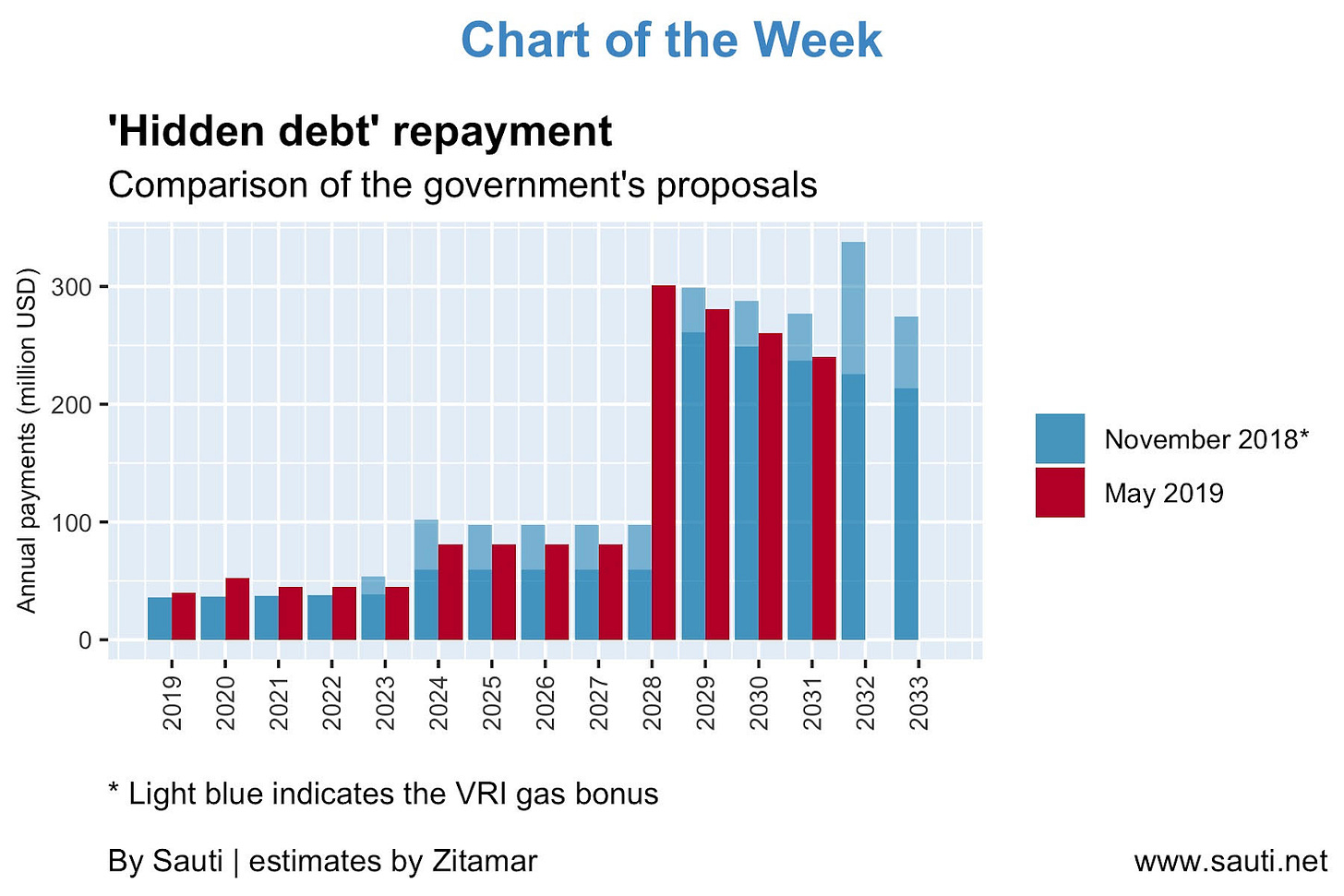

Good morning. The latest restructure proposal for Mozambique’s Eurobond will cost the country less in dollar terms than the agreement reached, in principle, last November — even without counting the gas-linked Value Recovery Instrument, which has now been done away with.

However the creditors are now getting their full $900 million back two years earlier than they would have under last November’s agreement, and higher payments every year — starting this year — through to the end of the deal in 2031, peaking in 2028 at more than $300 million. If Mozambique’s LNG projects don’t progress on schedule from here on in — and LNG projects have a tendency not to — Mozambique may have to borrow more in order to keep up its repayments on these new bonds — so it is still too soon to say how much this restructure will end up costing.

SEE: Gas hook taken out of Mozambique tuna bond

But should Mozambique be bothering to restructure these bonds at all, in the light of the Constitutional Council making official this week what most people have known all along: that the sovereign guarantee for EMATUM violated the country’s constitution?

The widely accepted reason for the current Mozambique government’s determination to pay the bond — while disowning the ProIndicus loan, which was guaranteed under identical circumstances as EMATUM — is that it wants to get out of their state of default to be able to sell more debt to finance national oil company ENH’s participation in the Rovuma Basin LNG projects.

Civil society coalition FMO welcomed the new proposal last week — while maintaining their position that the bonds should be disowned entirely.

However, if Mozambique is ultimately going to repay the debt, last November’s proposal looks better for the country than this one. For a country as vulnerable as Mozambique is to the resource curse, the more of its obligations that it can link to its volatile and unpredictable future resource revenues — through an instrument like the VRI — the better. They are essentially unearned ‘rents’ that, unlike the relatively predictable existing tax base, have the potential to destabilise the economy. Mozambique should let the country’s creditors take the risk, and potential upside, of those revenues where possible — and protect its regular budget as far as it possibly can.

More importantly, Mozambique should not borrow to allow ENH to take equity stakes in the Area 1 and 4 LNG projects. The Mozambican economy, and state revenues, will inevitably become highly correlated with these rich but finite gas projects over the coming two decades, even without paying billions of extra dollars to have ENH as a shareholder.

The Mozambique government has already risked the economy once, borrowing $2 billion based on offshore gas projects that it barely understood. Before it has even started its recovery, it now looks to be willing to risk it again.